When people say that Biden is the worst president in history, remind them that he doesn’t yet have the Blue and Red States in open warfare. This article by Dave Brenner is enlightening.

On April 28 in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus, allowing indefinite detainment of political dissidents. The gesture provoked immediate controversy, ignited a constitutional crisis, and exacerbated political tensions in Maryland.

The move came after a series of events that plunged Maryland into the heart of the sectional crisis. As union troops marched through the neutral state of Maryland in April of 1861, a group of state militia forces – viewing the excursion through Maryland to be an invasion and violation of state sovereignty – fired upon the federal forces as they attempted to use the state’s railway system. Nonetheless, the event became known as the “Baltimore Riot of 1861” and “Pratt Street Massacre” in the North, and those killed and wounded became portrayed as martyrs to the union cause to prohibit seccession.

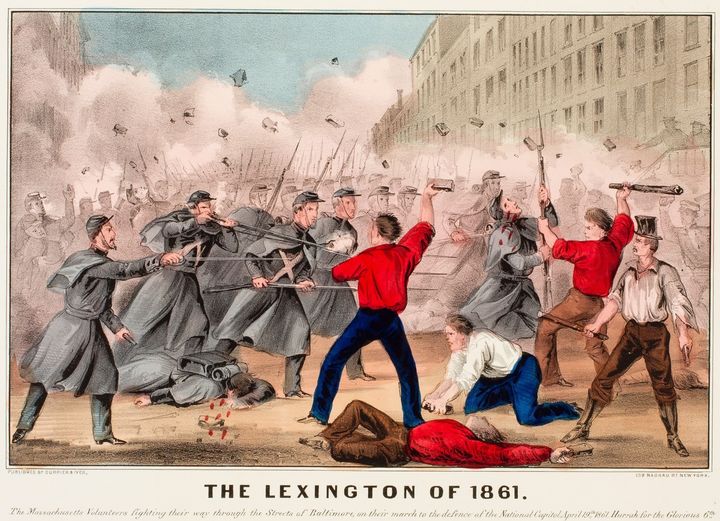

By all accounts, these circumstances forced Marylanders to choose sides, and the state populace became bitterly divided. Though the state legislature voted against seceding from the union on April 29, it also decided to disable northern rail links and made a formal request to the president to evacuate federal troops from the state. In response to the bloodshed, Maryland native James Ryder Randall wrote “Maryland, my Maryland” to support southern solidarity and condemn the Lincoln administration. Furthermore, local newspapers quickly began to dub the situation the “Lexington of 1861.”

By suspending habeas corpus, the president initiated a constitutional crisis. According to the United States Constitution, the Great Writ cannot be suspended unless “in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion,” and the forces in Maryland purported that they were simply resisting the same. Furthermore, the power is noted only in Article 1, which is confined to the enumerated powers of Congress and their limitations. Because the Lincoln assumed the authority to suspend habeas corpus rather than Congress, his deed was viewed as a bold-faced usurpation.

After suspending the writ, the Lincoln administration arrested and detained many military and civil officers from Maryland. Among them was John Merryman, a Lieutenant in the state militia tasked with disabling state railroad bridges, such that they could not be used by union soldiers. In addition, the president’s agents had Baltimore’s mayor, police chief, Board of Police, entire city council, and sitting US Congressman Henry May arrested and sent to Fort McHenry without charges.

The controversial arrests culminated in the case of Ex parte Merryman, where Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Roger Taney opined that Lincoln’s arrests were blatant usurpations. “The President, under the Constitution and laws of the United States,” he declared, “cannot suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, nor authorize any military officer to do so.” Though public jubilation followed the opinion, its impact was limited. The Lincoln administration ignored the ruling, and according to historian Thomas DiLorenzo, attempted to place the Chief Justice himself under arrest.

After the mounting opposition to the military presence and presidential administration grew throughout the summer of 1861, the president doubled down on the policy by placing one-third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly under house arrest. Per the president’s order, the decision was carried out for fear that the assembly “would aid the anticipated rebel invasion and would attempt to take the state out of the Union.” The Lincoln administration followed the order by imprisoning presiding circuit court judge Richard Bennett Carmichael in November, due to his public criticism that administration’s arrests had been arbitrary, unconstitutional, and immoral. The federal troops that arrested Carmichael beat him into unconsciousness while his court was in session, igniting even more public outcry.

Even former president Franklin Pierce, who desperately sought to arrange a compromise to avert bloodshed on the eve of war, viewed the situation as impetus to attack the president. Professing that a “reign of terror” had overtaken the new administration, Pierce called Lincoln’s whimsical arrests “ruinous to the victors as well as the vanquished.” In a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, he described the federal policy in Maryland as “the worst form of despotism.”

Ultimately, Maryland remained divided throughout most of the war. After the Republican Congress finally gave its assent to the suspension of the writ in March of 1863, the state remained occupied by union forces throughout most of the war. The prolonged imposition of martial law raised the indignation of many Marylanders, including John Wilkes Booth – the eventual assassin of Lincoln. Unable to convene its legislature, the state officially remained in the union throughout the duration of the war, while permitting slavery under law – and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation specifically omitted the state from a list of states it applied to.

Note: Dave Benner is the author of Thomas Paine: A Lifetime of Radicalism and Compact of the Republic: The League of States and the Constitution, which are available for at: https://davidbenner.square.site